“Fragile” is not a word that comes to mind when I see Simone Biles flip or Katie Ledecky swim or the U.S. National Women’s Soccer team play. These Olympians are tough, fierce athletes with extraordinary strength and determination. Yet not so long ago, critics warned that women were too “fragile” to participate in competitive sports.

That’s what a 19-year-old Syracuse runner named Katherine Switzer heard when she wanted to run the 1967 Boston Marathon. Switzer persisted despite the warnings, and her determination helped change the course of women’s sports.

Born in Amberg, Germany, in 1947 (her dad was in the army), Switzer grew up running and playing basketball and field hockey in Fairfax County, Virginia, outside of D.C. As a student at Syracuse, she trained with the men’s cross-country team because the university did not offer women’s track. (Few colleges did — not until long after the 1972 passage of the Title IX amendment to the 1964 Civil Rights Act did higher education begin to offer women’s sports in earnest.) She asked the “kindly old coach,” Arnie Briggs, to help her train for the 1967 Boston Marathon, which no woman had ever run before. Briggs refused at first, arguing that women “too fragile” to survive running such distances.

Briggs was not just some narrow-minded misogynist with outlandish beliefs — his attitude was rather typical for mid-20th century America. Despite the physical toughness required to give birth, raise children, and work on farms or in factories, women were dismissed as too “delicate” for sports. One leading 19th century theory argued that sports would drain women of the limited amount of energy they had in their bodies. Other critics warned that playing sports made women “unattractive” and would destroy their reproductive systems.

As a result, officials placed significant limits on the sports women were allowed to play. In running, for example, no major marathon (including the Olympics) allowed women to compete. Switzer wanted to change that. She eventually convinced Briggs to help her train and registered for the race using her initials, K.V. Switzer.

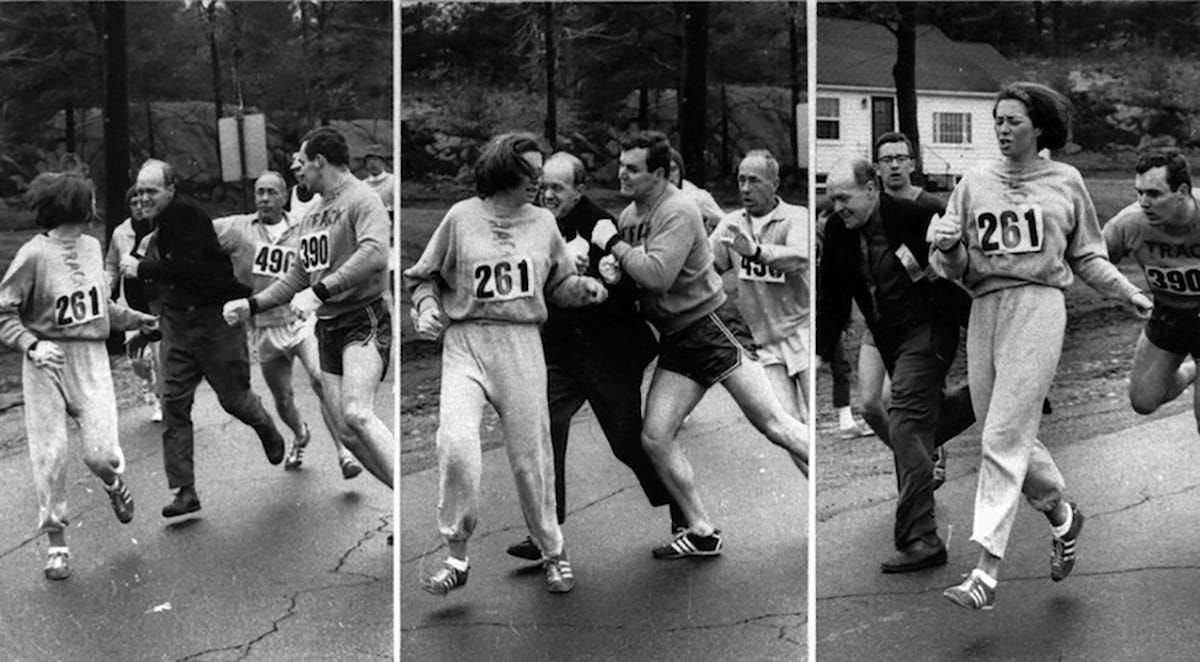

On April 19, 1967 — a fine Spring day in Boston featuring sleet, wind, and some snow for good measure — Switzer pinned #261 to her sweatshirt and lined up with her coach Briggs, her boyfriend (a 235-pound hammer thrower named Big Tom Miller), and a pack of male runners, many of whom offered encouraging words of support. About four miles into the race, she heard the ominous sound of dress shoes clomping quickly on the pavement behind her. She turned to see, in her words, “a huge man with bared teeth…set to pounce.” It was Jock Semple, co-director of the marathon. “Get the hell out of my race and give me those numbers!” he screamed as he pawed wildly at Switzer’s bib.

Big Tom bodychecked Semple out of the way.

The whole scene took less than a minute, but it transpired right in front of the press van and was captured by photographer Henry Trask. The world would see the horrific face of misogyny plastered across newspapers nationwide. (The photo was later included in Life Magazine’s 100 Photos That Changed the World).

The moment “radicalized” Switzer, she later recalled, and forever changed women’s sports. Before the race, “I wasn’t running Boston to prove anything; I was just a kid who wanted to run her first marathon.” But Semple’s rage shook her, fueling her determination to finish. “If I quit,” she thought to herself, “it would set women’s sports back, way back, instead of forward.” As they kept running, she told her coach Briggs, “No matter what, I have to finish this race…even on my hands and knees.” And she did, with a time of 4 hours and 20 minutes.

Though she had finished well ahead of many men (as had another woman, Bobbi Gibb, the year before – but Gibb had done so as a “bandit” who ran unofficially), race officials adamantly refused to change the rules about allowing women to compete. Switzer lobbied for years before they relented. The New York City Marathon began allowing women to compete in 1970, and the Boston Marathon followed suit two years later.

But it would take another decade before the International Olympic Committee dropped its opposition to hosting a women’s marathon. Not until the 1984 Games in Los Angeles were women allowed to run an Olympic marathon — and Mainer Joan Benoit (below) brought home the gold for the United States.

Switzer went on to become a leading activist for equality in sport and was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 2011 for her role in helping tear down barriers to women athletes.

Photo credits: Associated Press

Great Story about a great woman.

Thrilled to be in touch with you in this way. Your two parents will always be two of our favorite people. I’m so proud to know you! Marcella (and Pete) Ruch

(We haven’t been in touch but I’ve rejoiced in your wonderful marriage and family. Family is the icing on the cake of life.)