About 20 years ago (in a different lifetime, it seems), my friend Shawn Raymond and I spent several years working to build a U.S. Public Service Academy as a civilian counterpart to the five U.S. military service academies. As the son of a Foreign Service officer and a civilian doctor at Walter Reed Army Medical Center, I appreciated the value of public service, and I envisioned a flagship national institution that would inspire a new generation to serve America. Modeled on the military service academies, the Public Service Academy would offer a rigorous, federally-supported undergraduate education followed by five years of mandatory service to the country. In short, we wanted to build a civilian West Point.

(Spoiler alert: The Public Service Academy never got built. Long story for another time.)

Somewhat to my surprise, some of our biggest supporters were alumni, faculty, and administrators of the military service academies. Rather than see a civilian counterpart as a threat or an imposter, they embraced our effort. These were people who had dedicated their lives to defending our country, and they shared our sense of mission. They understood that young people yearned to be part of something larger than themselves, but not everyone wanted to serve in the military.

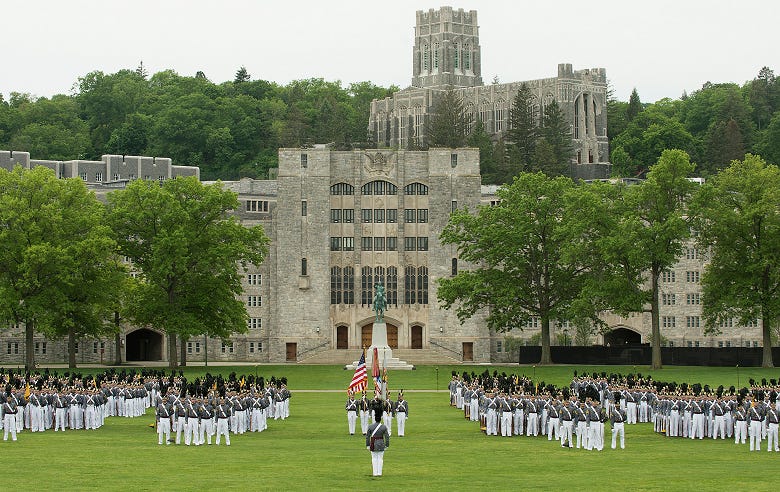

Lt. Gen. Dave Palmer, former superintendent of West Point, invited me to visit campus to talk with students and faculty about their experiences. I was thoroughly impressed – and grateful that this place existed.

Perched high atop a serpentine curve in the Hudson River, West Point served as a strategic choke point during the Revolutionary War (Benedict Arnold tried to turn the fort over to the British in 1780, earning everlasting ignominy). As president, George Washington proposed using the site for a military academy, envisioning a national institution that would not only train officers in the art of war but also instill in them respect for the Constitution and the ideals of the Revolution. After years of partisan squabbling, Congress established the academy in 1802.

Step foot on campus, and you know immediately that West Point is special. The cadets may be the same age as college students elsewhere, but they are different: more mature, more confident, more responsible. They share an abiding sense of purpose — they know why they are there, and they understand that the American people have invested in their development as future military leaders. There’s a sense of belonging and mutual obligation that is absent in most other colleges, a feeling that “we are all in this together.” Most impressively, every adult at West Point takes a deep interest in making sure that every one of the cadets succeeds. They knew each cadet inside and out, not just as students but as whole human beings.

Is West Point for real? Writer David Lipsky was skeptical. Lipsky was a higher education reporter for Rolling Stone in the late 1990s, and his editor pushed him to do a piece on West Point. With no military background and little interest in the subject, Lipsky reluctantly agreed. What he found blew him away. He had visited dozens of universities, but nowhere did he find young people as engaged, enthusiastic, and just plain happy as the West Pointers. Yes, they complained and schemed and goofed around, but they were genuinely committed to a higher cause that infused everything that they did. Lipsky wound up spending four years following the Class of 2001, which graduated just months before September 11. He tells their story in an incredible book, Absolutely American.

The ethos of West Point that so impressed Lipsky (and me) traces its roots to one determined man: Sylvanus Thayer.

For more than a decade after its founding, the new academy flailed aimlessly. It cycled through a series of mediocre leaders who failed to impose discipline, establish a curriculum, or provide a sense of purpose. The school’s paranoid fourth superintendent, Alden Partridge, nearly destroyed the fledgling institution when, convinced of a conspiracy against him, he arrested the entire faculty and started teaching all the courses by himself. President James Monroe intervened, fired Partridge, and selected Sylvanus Thayer to take charge.

It was an inspired choice.

Thayer was just 32, but he already had established himself as a careful student of war. Born into a farming family in Braintree, Massachusetts, in 1785, he graduated from Dartmouth in 1807, then breezed through West Point’s thin engineering coursework in a year. While serving as an engineer during the War of 1812, he became convinced that American military leaders were woefully under-prepared and unprofessional. After the war, he spent two years (on the Army’s dime) studying military schools in England, Germany, Holland, and France — he was particularly impressed with the French military academy, L’Ecole Polytechnique. He devoured books on military strategy, mathematics, and engineering, and he bought more than 1,000 volumes that later became the core of West Point’s library.

Thayer returned home in 1817 with high hopes of bringing European professionalism and standards to his alma mater. But he had inherited a mess. In the wake of his predecessor’s departure, the campus was in chaos.

His first priority was to establish discipline. He expelled dozens of disorderly cadets, including prominent sons of the wealthy elite, and made it clear to those who remained that it was an “erroneous and unmilitary notion” to think that they could “intrude their views and opinions with respect to the conduct of the Acad’y.” Henceforth, West Point would be run on Thayer’s terms, which meant 15-hour days jammed with drills and classes.

Next he tackled academics. While other American colleges offered a classical curriculum laden with Greek and Latin, Thayer developed a four-year course of study that emphasized math and physics, as well as military ethics. He slashed class sizes, mandated daily recitation, offered more credit for challenging courses, and required summer enrichment rather than the traditional furloughs. He expected faculty members to provide weekly progress reports on every student, and he invited outside visitors to observe and assess the school’s efforts. West Point quickly became the nation’s premier engineering school.

Perhaps most importantly, Thayer established a new ethos that bound cadets together with a shared sense of purpose. “The honor of our country,” he wrote in 1818, “must receive its tone and character from the initial formation of its officers.” He established the Academy’s honor code and held cadets to it. Aware that the academy’s critics worried about a “military aristocracy,” he abolished favorable treatment for the elite and required all cadets, no matter their background, to live simply on their skimpy cadet allowance. Living, studying, and drilling together in harsh conditions, cadets developed powerful bonds.

Though Thayer did not coin West Point’s classic motto — “Duty, honor, country” was adopted in 1898 – he lived its values and embodied the virtues he hoped to instill in his students. A lifelong bachelor, he was married instead to the institution and was devoted to the success of its cadets. Intense and strict, fastidious in dress and manner, he commanded respect through his very being and bearing.

Under Thayer, West Point did not become a replica of the European academies. Its culture was uniquely American. “This culture stressed not only traditional Roman military virtues, such as loyalty and honor, but also individual accountability and thoughtful allegiance to the highest of ethical standards and to the Constitution and the rule of law,” wrote West Point historian Wesley Allen Riddle. “Thayer recognized the importance of educating officers to give their allegiance to the Constitution and American ideals rather than to individual leaders.”

Not everyone appreciated that ethos. His predecessor, Alden Partridge, spent years sabotaging his efforts, claiming that Thayer’s approach was “effeminate and pedantic.” But Thayer built a network of allies within Congress and after a decade of leadership he had transformed the wayward institution into what President Andrew Jackson called “the best school in the world.”

Yet Jackson would prove to be a fickle friend. Despite the public praise, Jackson and his supporters were suspicious of a professional army and thought West Point was a playground for children of the elite. He undermined Thayer’s authority by overruling his disciplinary decisions – expelled cadets knew they could win reinstatement by appealing to the president. Jackson expected Thayer, like everyone else, to bow to presidential authority. Thayer stood his ground, insisting that West Point’s credibility depended on its adherence to principle. He parried the president through one term, but he resigned his post after Jackson was reelected in 1832.

In his 15 years as superintendent, Thayer did for West Point what Chief Justice John Marshall did for the U.S. Supreme Court at roughly the same time: they both took listless, ineffective institutions and infused them with new energy and purpose. West Point isn’t perfect – no institution is – and over the years it has struggled to adapt to shifts in our culture and politics. But it remains committed to the ideals that Sylvanus Thayer worked to instill in cadets two hundred years ago. Thayer’s spirit of disciplined conduct, academic rigor, and service above self endures.

Sources

Sidney Forman, West Point: A History of the United States Military Academy (1950)

Herman Hattaway and Michael D. Smith, “Sylvanus Thayer,” American National Biography (1999)

James William Kershner, “Sylvanus Thayer: A Biography” (Ph.D. Dissertation, West Virginia University, 1976)

Spencer Klaw, “Sylvanus Thayer: The Man Who Made West Point,” American Heritage, Vol. 29, No. 4 (June/July 1978)

David Lipsky, Absolutely American: Four Years at West Point (2003)

Wesley Allen Riddle, “Duty, Honor, Country: Molding Citizen-Soldiers,” Policy Review, Issue 87 (Jan/Feb 1998): 48.

Elizabeth D. Samet, A Soldier’s Heart: Reading Literature Through Peace and War at West Point (2007)

Terrific piece. For similar musings about the ethos at West Point and the Civil War history of the institution, see the excellent book, "Robert E. Lee and Me" (2021), by Ty Seidule, longtime head of the History Department at West Point.

Great article, Chris. I think Thayer Academy in Braintree was another of his creations. West Point sounds amazing. I do wish they'd produced a few more generals who realized Vietnam was a lost cause (at best) and were able to convince LBJ of that. I wonder what Thayer would have made of that war. Since this forum is for "What's Gone Right", I'll leave it at that and hope that your U.S. Public Service Academy is built and you become the next Thayer.