Thanks for reading “What’s Gone Right”! If you enjoy this article, add a “like” or a comment at the bottom and share the link with your friends.

When my mother died a few years ago, my heartbroken brothers and I had to sort through a lifetime’s worth of accumulated memories embodied in, for lack of a better word, her stuff. Much of it was just plain junk — old magazines, worn-out shoes, crumpled linens. Some of it could be donated — books, kitchenware, sturdy furniture.

Then there were things that told our family’s story: a high school yearbook featuring my 17-year-old mom talking about her future plans, yellowing black-and-white photos of people we didn’t recognize, keepsakes from our years living abroad. We definitely couldn’t throw such precious items out. But how could we store them? And where?

My eldest brother embraced the task. He spent months sorting through old shoeboxes, filing pictures and papers, and labeling everything in airtight plastic containers. He keeps it all stored away, safe from the elements. It was and is yeoman’s work, all to preserve a single family’s story.

What about the narrative of a community? Or the story of a state? Or a nation?

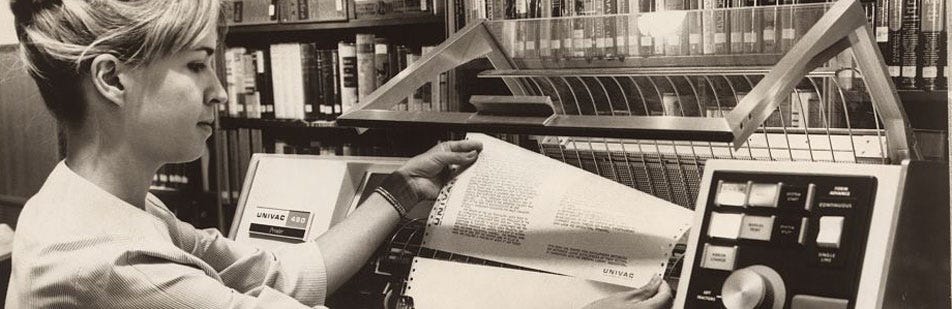

That’s the role of public archives. In communities across the country, archivists collect, catalogue, and conserve millions of letters, pictures, newspapers, diaries, movies, ads, pop songs, blog posts, and ephemera (one of my favorite words in the English language). Archivists know that once they’re gone, they’re gone. It’s their duty to preserve the evidence of what we have done in our time here on Earth, so that we and our descendants can tell our communal stories.

When I was in graduate school and in a hurry to finish my degree, I remember chafing at the restrictions that archives placed on researchers, particularly at the Library of Congress and other major institutions. I had to fill out this piece of paper, then get that kind of ID, then submit this kind of request, then wait while someone disappeared into the bowels of the building to find the document I wanted. It seemed to take so long!

But then, the archivist would return with some neatly labeled trove of documents. Opening the box was like opening a window into the past. While working on Chocolate City, I spent many days in the dank, drafty National Archives sifting through old abolitionist petitions and other 19th century documents, immersing myself in a world so distant from my own. It was marvelous! Archivists made that experience possible, for me and for countless researchers.

In the past two decades, archivists have spent innumerable hours digitizing their collections, making them accessible to anyone, anywhere. As I sit here at my dining room table in Maine, I can download Dorothea Lange’s pictures documenting the Great Depression, sift through the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission files from the 1950s and 60s, or listen to a 1980 Johnny Cash concert at Soledad State Prison in California.

The vision and the sheer amount of work that it takes to create and preserve an archive are breathtaking and under-appreciated. A historian’s tip of the cap to the legions of archivists who make our work possible. Thank you.

Excellent, Chris. Thank you.